Family

Young, single and what about it?

This article looks at the sharp rise in young Chinese happy to live by themselves; the next at old people less happy to do so

Aug 29th 2015 | BEIJING | From the print edition

来源:Economist

翻译:Z.K.

IN HER tiny flat, which she shares with two cats and a flock of porcelain owls, Chi Yingying describes her parents as wanting to be the controlling shareholders in her life. Even when she was in her early 20s, her mother raged at her for being unmarried. At 28 Ms Chi took “the most courageous decision of my life” and moved into her own home. Now 33, she relishes the privacy—at a price: her monthly rent of 4,000 yuan ($625) swallows nearly half her salary.

在她的小公寓里,Chi Yingying和两只猫还有一群瓷器猫头鹰生活在一起。她说她的父母想控制她的生活,甚至在在20刚刚出头的时候,她的母亲就抱怨她还不结婚。28岁的时候,Chi小姐终于搬出了父母家,搬到了自己家生活,她称之为“生命中最勇敢的决定”。现在,Chi小姐33岁了,她很享受这种独处的生活,代价是她要付每个月4000元的房租,这几乎是她月薪的一半。

In many countries leaving the family home well before marriage is a rite of passage. But in China choosing to live alone and unmarried as Ms Chi has done is eccentric verging on taboo. Chinese culture attaches a particularly high value to the idea that families should live together. Yet ever more people are living alone.

在许多国家,离开父母是婚前的成年礼。但是在中国,选择独自生活,不结婚—就像Chi小姐所做的一样—-被认为是非常古怪甚至是接近禁忌的。在中国文化里面,家人应该住在一起的这种观点是。。。。但是现在越来越多的人选择独自生活。

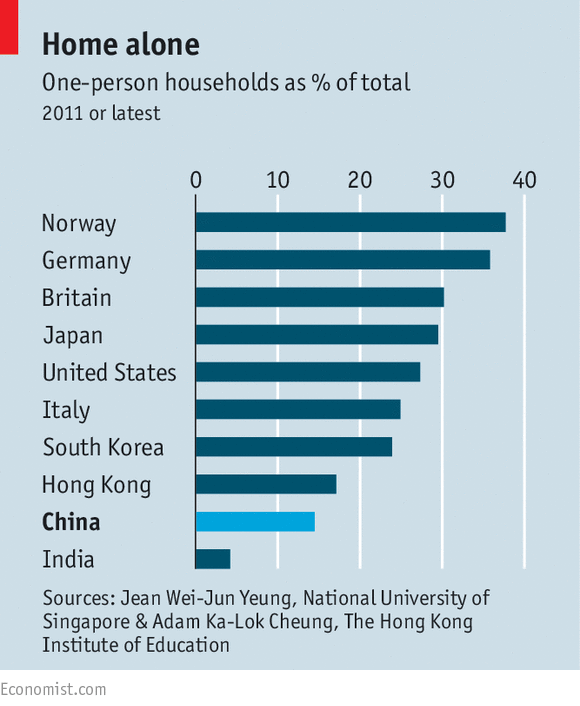

In the decade to 2010 the number of single-person households doubled. Today over 58m Chinese live by themselves, according to census data, a bigger number of one-person homes than in America, Britain and France combined. Solo dwellers make up 14% of all households. That is still low compared with rates found in Japan or *** (see chart), but the proportion will certainly increase.

在2001到2010十年间,中国单人住户的数量翻了一倍。现在,超过58,000,000中国人选择独居生活,根据人口普查数据显示,这个数字已经超过了美国,英国和法国独居人数的总和。独居家庭占到了所有家庭的14%,跟日本和台湾相比,这个比例仍然比较低,但是这个比例肯定会增长的。

The pattern of Chinese living alone is somewhat different from that in the West, because tens of millions of (mainly poor) migrant workers have moved away from home to find work in more prosperous regions of China; many in this group live alone, often in shoeboxes. Yet for the most part younger Chinese living alone are from among the better-off. “Freedom and new wealth” have broken China’s traditional family structures, says Jing Jun of Tsinghua University in Beijing.

中国人独居的方式跟西方国家有所不同,因为数以千万计的农民工(大部分都是穷人)离开家乡,到中国比较富裕的地区寻找工作。这个群体的大部分都是独居,而且住在一个很小的房子里。但是,大部分年轻的独居者都来自较为富裕的家庭。清华大学的 Jing Jun 说,“自由和新财富”打破了中国传统的家庭结构。

The better-educated under-30-year-olds are, and the more money they have, the more likely they are to live alone. Rich parts of China have more non-widowed single dwellers: in Beijing a fifth of homes house only one person. The marriage age is rising, particularly in big cities such as Shanghai and Guangzhou, where the average man marries after 30 and the average woman at 28, older than their American counterparts. Divorce rates are also increasing, though they are still much lower than in America. More than 3.5m Chinese couples split up each year, which adds to the number of single households.

受过良好教育的三十岁以下的人们,他们越有钱就越喜欢独自生活。中国的富人现在越来越多的是非丧偶的年轻独居者:在北京,五分之一的家庭只住着一个人。结婚年龄现在在增加,特别是在大城市,比如上海和广州,在这些城西,男人平均婚龄是30岁之后,女性平均婚龄是28岁,比美国的同龄人要晚。离婚率也在增长,虽然与美国相比还是要低得多。中国每年超过3,500,000中国夫妇离婚,这也增加了单人住户的数量。

For some, living alone is a transitional stage on the way to marriage, remarriage or family reunification. But for a growing number of people it may be a permanent state. In cities, many educated, urban women stay single, often as a positive choice—a sign of rising status and better employment opportunities. Rural areas, by contrast, have a skewed sex ratio in which men outnumber women, a consequence of families preferring sons and aborting female fetuses or abandoning baby girls. The consequence is millions of reluctant bachelors.

对于某些人来说,独居是结婚,再婚或者家人团聚的过渡阶段。但是,对于越来越多的人也可能是永久的状态。在城市,许多受过良好教育的都市女性保持单身,这往往是晋升和获得更好的就业机会的一个积极的选择。相比之下,在农村地区,由于重男轻女观念的影响,导致男女比例平衡,男性比女性多,结果就是数以百万计的男性不得不单身。

In the past, adulthood in China used, almost without exception, to mean marriage and having children within supervised rural or urban structures. Now a growing number of Chinese live beyond prying eyes, able to pursue the social and sexual lives they choose.

过去,在中国成年就意味着结婚和在监管下的农村或城市生小孩,几乎没有例外。现在,越来越多的年轻人脱离了窥探的眼睛,追求自己选择的社会和性生活。

In the long run that poses a political challenge: the love of individual freedom is something that the Chinese state has long tried to quash. Living alone does not have to mean breaching social norms—phones and the internet make it easier than ever to keep in touch with relations, after all. Yet loosening family ties may open up space for new social networks, interest groups, even political aspirations of which the state may come to disapprove.

长此以往,这种情况会带来政治挑战:对个人自由的追求一直以来是中国政府试图打消的。独居并不一定意味着违反社会规范,毕竟,手机和互联网让人们比任何时候都更容易保持联系。然而,家庭关系的淡化可能会为新的社会网络,利益集团,甚至是政治诉求的形成提供条件,这些也许是国家所不允许的。

For now those who live alone are often subject to mockery. Unmarried females are labelled “leftover women”; unmarried men, “bare branches”—for the family tree they will never grow. An online group called “women living alone” is stacked with complaints about being told to “get a boyfriend”.

现在,那些独居的人往往受到嘲笑,未婚女性被打上“剩女”的标签,未婚男性被称为“光秃秃的树枝”,因为在家族里面,这些“树枝”不会再开枝散叶了。网上一个叫做“女人独自生活”的组织,充斥着“有男朋友了”的抱怨。

Even eating out can be a trial, since Chinese food culture is associated with groups of people sharing a whole range of dishes. After repeated criticism for dining alone, in 2014 Yanni Cai, a Shanghai journalist, wrote “Eating Alone”, a book on how singletons can adapt Chinese cuisine to make a single plate a meal in itself. According to tradition, even a frugal Chinese meal comprises “four dishes and one soup”. A single diner is likely to find that rather too much to stomach.

外出吃饭可以作为一个尝试,因为中国饮食文化是与一群人共享食物息息相关的。在单独吃饭屡遭批评之后,2014年,上海记者Yanni 写了一本书《一人食》,这本书介绍单身如何适应中国菜,做一盘菜就可以解决一顿饭。按照传统,即便是节俭的中国家庭一顿饭也包含”四菜一汤”。但是对于独居的人来说,这有点太多了。

京公网安备 11010502036488号

京公网安备 11010502036488号